May 2021 marks the 100th anniversary of the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, the first immigration law in the United States to establish an immigration quota system based on national origins. As the “emergency” in its name suggests, the act was part of the American reaction to the immense tumult that accompanied the end of the first World War. It reflected a broader effort at retrenchment in the face of change, a quest for “normalcy,” in the words of victorious 1920 presidential candidate Warren G. Harding. Yet a long-gestating effort to restrict the immigration that accompanied the immense economic changes of the industrial revolution preceded the act. For years, disparate but at times overlapping groups inspired by labor concerns, anti-Catholicism, and pseudoscientific racial “science” had all perceived this immigration as a potential threat.

The intertwined concerns over race and labor can be seen in a predecessor to the Emergency Quota Act, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The Exclusion Act took aim at Chinese labor, although distinguishing between laborers and non-laborers was difficult and often reflected racial assumptions on the part of those doing the distinguishing. One longtime proponent of restricting Chinese labor was Dennis Kearney, himself an Irish immigrant and founder of the Workingman’s Party, who ended every speech he made by calling for the Chinese to be ejected.

The eventual success of this exclusion campaign, however, did not deter the millions of immigrants arriving from southern and eastern Europe in the 1800s and early 1900s. While anti-Chinese sentiment was particularly strident, other labor leaders, such as the American Federation of Labor’s Samuel Gompers, agitated against unrestricted immigration in general, for fear of its effect on wages. Like Kearney, Gompers was himself an immigrant. However, for several reasons, Gompers viewed the “new” immigrants in the 1890s and 1900s as outside of the natural constituency of skilled laborers that the AFL worked to unionize. Many of the new immigrants were coming in as largely unskilled labor, and some immigrants, largely unaware of local conditions upon their arrival, had been used as “scabs” by business owners to break strikes. Differences in language and culture also inhibited organization. The International Workers of the World (IWW) did attempt to organize across skill-level and national lines, but this connection with the more radical of the labor unions contributed to the association of immigrants with political danger.

The Catholic identity of many of the new European immigrants was pointed to by several groups as a sign of the supposed danger posed to American institutions by the country’s changing demographics. Suspecting Catholics of allegiance to an outside power (the Pope), the American Protective Association railed against Catholic schools as a subversive threat to American democracy. The rejuvenated Ku Klux Klan, which spread beyond the former Confederacy as a political force in the 1910s and 1920s, also defined itself on its opposition to Catholicism in addition to its commitment to white supremacy.

Also supporting restriction were believers in the “science” that undergirded the eugenics movement, which held national identity as a racial feature. Perhaps most infamous of these was Madison Grant, who warned in The Passing of the Great Race (1916) that new immigrants from places like Poland or Italy could never assimilate to U.S. society and that “native Americans” – that is, largely Protestant, white Americans who traced their ancestry to northern and western Europe – would face an existential risk of destruction. Grant predicted that “in large sections of the country the native Americans will entirely disappear . . . New York is becoming a cloaca gentium [sewer of nations] which will produce many amazing racial hybrids and some ethnic horrors that will be beyond the powers of future anthropologists to unravel.”

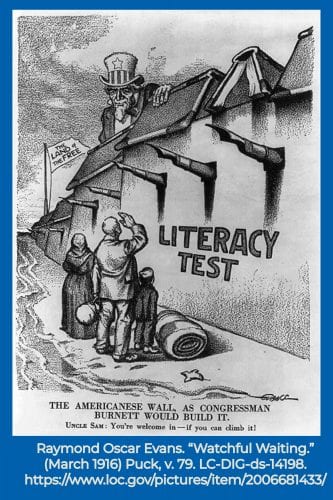

Aside from asserting a greater role in immigration for the federal government, however, and making the Chinese Exclusion Act permanent in 1904 after a series of renewals, the concerns of labor, anti-Catholic agitators, and eugenicists had not stopped the flow of immigrants in the early 20th century. In 1911, a Congressional commission on immigration, although sympathetic to immigrants, concluded that both a literacy test and a quota system were needed to stem the flow of immigrants. The literacy test requirement passed in 1917, over President Woodrow Wilson’s veto, but the quota system did not. Instead, the massive mobilization of World War I saw the U.S. government appeal to the communities of new immigrants to serve in the U.S. armed forces.

In the aftermath of the war, however, the political situation was different. Despite being in combat for a relatively short time and losing far fewer people than the other great powers, U.S. forces still suffered significant casualties. The influenza pandemic of 1918-19 killed hundreds of thousands, and a series of strikes added to a palpable sense of instability. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, in particular, inflamed U.S. opinion against the perceived threat of foreign influences. Attorney General Mitchell Palmer, in justifying a wave of deportations in response to anarchist bombings, argued that “communism in this country was an organization of thousands of aliens who were direct allies of Trotzky (sic). Aliens of the same misshapen caste of mind and indecencies of character…”

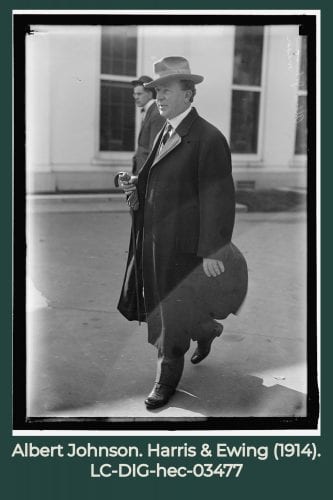

The sense of crisis persisted past 1919, and at the end of 1920, Representative Albert Johnson introduced a bill to ban all immigration for two years. After an amendment reduced the ban to 14 months, the House passed the bill 296 to 42, but it was defeated in the Senate. However, there was support for Senator Paul Dillingham’s (R-VT) suggestion of a quota-based restriction system. Johnson, first elected in 1912, had dedicated his career to immigration restriction and, while preferring the moratorium, adopted the quota suggestion to bring the necessary senators aboard. The resulting legislation allowed for 350,000 entrances to the United States a year, with a quota by nation reflecting the population of the 1910 census, meaning that for European countries, 55% of quota allotments went to northern and western Europe. The exclusion of China was continued and extended to other east Asian countries. Despite a pocket veto from Wilson, the legislation was eventually signed by Warren G. Harding soon after he entered office.

Ultimately, the 1921 Act did not have the impact its advocates hoped for, leading to a more extreme bill in 1924, co-sponsored by Johnson, which lowered the overall number of entrances per year and specified new quotas based on the 1890 census. While the 1921 and 1924 Acts represent in some ways the high-water mark for immigration restriction in the 20th century, recent historians of immigration have stressed that these were not unalloyed victories. The quotas were delayed in the face of opposition from business interests, not going into effect until the presidency of Herbert Hoover. The quotas were also revised to reflect the 1920 census based on the decision of a Quota Commission established by Congress and in an atmosphere of continuing debate and struggle over the 1924 act.

Most importantly, the acts did not apply to the Western hemisphere. Here, the racial panic of eugenicists at the consequences of workers from Mexico coming into the United States did not stop the flow of labor. The push-and-pull dynamics of the economic cycle and the crises of the Great Depression and World War II had a dramatic impact on immigration in the American Southwest, but the advocates of restriction found the economic dynamics on the southern border already too entrenched to challenge with the quota laws.

While not as overwhelming a victory for the advocates of immigration restriction as it might appear, the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 did reflect the tilt of American politics towards retrenchment in the 1920s. The goals of the legislation in 1921 and 1924 were ultimately repudiated by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, but restrictions in numbers and by region remained. The imposition of a quota set a precedent in U.S. immigration law. Nor did the lack of an overwhelming victory for the restriction advocates mean there were not negative consequences. Most famously, the quotas imposed led to the rejection of some of the Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany in the 1930s, to tragic results.

The 1921 Emergency Quota Act was a key moment in the continuing struggle over power and identity rooted in questions of immigration, establishing a major precedent in immigration restriction. Despite the ebbs and flows of policy, that precedent continues to exert an influence to the present.

Kristofer Allerfeldt, “‘And We Got Here First’: Albert Johnson, National Origins and Self-Interest in the Immigration Debates of the 1920s,” Journal of Contemporary History 45:1 (Jan., 2010), 7-26.

Katherine M. Donato and Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes, “The Landscape of U.S. Immigration: An Introduction,” The Russell Safe Foundation Journal of Social Sciences 6:3 (Nov., 2020), 1-16.

David Gerber, American Immigration: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Mae M. Ngai, “The Architecture of Race in American Immigration Law: A Reexamination of the Immigration Act of 1924,” Journal of American History 86:1 (Jun., 1999), 67-92.